Press

Who’s Here: Barbara Goldsmith Writer & Philanthropist

Dan’s Papers

July 12, 2013

By Dan Rattiner

Barbara Goldsmith is a celebrated New Yorker who has summered in the Hamptons for more than half a century. She’s well-known in the literary world, not only for her books, some of which have risen to #1 on The New York Times best seller list, but also for her earlier career when as a recent, brilliant graduate of Wellesley College, she began writing about the art world, civil rights and celebrity, ushering in the style of New Journalism. She is also a well-known New York philanthropist.

Barbara has had a wonderful, exciting life, and I was pleased to have lunch with her recently, where we got into a long discussion about it.

Her father’s father emigrated from the Russian-Polish border at the turn of the 20th century to the Lower East, where he sold goods from a pushcart and, according to her father, moved from apartment to apartment with his family of eight kids whenever the rent came due.

Her father, the youngest, while working during the day, spent 13 years studying at night to gain an education. He got a degree in accounting and opened an accounting firm. Then, when the law changed so that he could not give tax advice, he went back to night school and became a lawyer. By the time Barbara and her sister were born, he was extremely affluent. Among other properties, he owned more than 50% of Pepsi Cola and was its chairman. He was also, along with David Rockefeller, able to donate a considerable amount of land he owned on the East Side of Manhattan to make it possible for the United Nations to have its headquarters in New York.

Barbara’s mother, Evelyn, came from more fortunate circumstances. Her father, Reuben Cronson, was Chief of Surgery at New York Presbyterian Hospital.

“Early on,” Barbara said, “our parents told us that if you were privileged, you’re obliged to give back to society. They also talked about the importance of family and a good education. History was often spoken of at our dinner table. It was one of my father’s favorite subjects. I recall, when I was seven, I had to learn Latin. That will give you an idea of how things were for me then.”

One thing her parents could not agree on, however, was where she and her sister should go to school. Her mother had gone to Miss Hewitt’s classes. Her father had gone to public school. Eventually, he prevailed in this argument.

“I went to Public School 93 on Central Park West at 92nd,” Barbara said. “But then, one day when I was seven, I came home with head lice. So that was the end of New York City public school. Soon thereafter we moved to New Rochelle, which had excellent public schools.”

“So head lice was why you moved

to New Rochelle?”

“Well, yes,” she said. We both laughed. “But believe me, there’s plenty of head lice in both public and private schools.”

At the Mayflower Grammar School in New Rochelle, when she was nine years old, something happened that convinced her she should study to become a writer.

“We had been asked to write a composition. I wrote an essay about a character named Jackson the Jester (who made people happy, but wore an iron collar around his neck). When I read it to the class, some of the students were so moved they began to cry. It made a great impression on me.

“I think I didn’t want people to know what I dearly wanted to do was write, so I did every other activity. But I wrote, too. I even edited the school newspaper. One day, my teacher sent a short story I wrote to a magazine called New Directions, and they published it. That did it.”

At Wellesley, she signed up to be an English major, and in her first class, her English professor asked everyone to write what they did over the summer. When she got her essay back, there was a big red C on it. And the comment under it said that there was a dangling participle and she needed work on learning her grammar.

“I went to my class advisor. I was in tears. If I stay in this class, I said, I’m going to lose my writer’s voice. I’m only 17 but I have a voice. If I stay, I might be a good writer, but people will not know it is me.”

The solution was for her to modify her major. She got a joint degree in English and Art History. With a joint degree, she did not have to take the course with this grammarian.

After graduation, she began looking for work at magazines. After several short stints, she got a job as the Assistant Entertainment Editor at Women’s Home Companion, a magazine that was designed to appeal to women as homemakers. She soon found out the magazine didn’t have an entertainment section. She began to try to make one.

“One day the magazine got a call from a public relations person for Clark Gable. They’d like the magazine to do a profile on him. Everybody was excited but upset at the same time. Who could do this? This was a magazine where there were recipes for noodle rings. Somebody said, ‘Let the kid do it!’ and so I did. After that, I interviewed Deborah Kerr, Audrey Hepburn, Carey Grant, Joan Crawford, Alfred Hitchcock, and then I thought, ‘I’m good at this, maybe I could interview who I want.’ So I interviewed Picasso, Marcel Bruer, I. M. Pei and Andy Warhol.”

This was in the 1960s. Warhol was not that well-known yet. Barbara wrote that some people said California would be the future of art, but that was not so. The future was Andy Warhol. That got her an invitation from Warhol to come over to the “Factory” he had on Union Square. She got to know everybody. She developed a longtime friendship with Warhol. Now she was writing pieces for Town & Country, Art News and The Herald Tribune and was an accepted New York journalist. Also, for the first time, she began, with a group of other writers, renting in the Hamptons in the summertime, mostly in and around Georgica in East Hampton. She remembers those days very vividly.

“I remember Arthur Penn built a movie theater in his basement, and we’d watch films there. I recall seeing Paul Newman in Left Handed Gun. I remember this shop run by Art and Bessie, where you could get pâté. They’d make their own, and you had to get there early in the week because later the pâté wouldn’t be good anymore. I remember the girls going to Anita Zahn’s Ballet School in what is now John and Jodi Eastman’s house. I recall this shop on Main Street in East Hampton where the woman would make your clothes. We’d walk the beaches and meet new friends. It was all so informal, I recall someone would say ‘wear a dress tonight because my mom is coming for dinner and didn’t want to see us in jeans.’”

Back in the city, Barbara worked for the New York section of The Herald Tribune and volunteered at the Museum of Modern Art. She reviewed a book written by Andy Warhol called From A to B and Back Again. She wrote about museum curator Henry Geldheizer in an article called “How Henry Made 40 Artists Immortal.” At the New York section of The Herald Tribune (the newspaper which would soon lose its struggle to stay in business), Goldsmith worked for Clay Felker, and when the Tribune collapsed he asked her to help buy the title “New York” from the newspaper. She did. In 1968 the magazine began with Goldsmith as one of the founding editors.

“I wrote a very controversial piece for New York about Viva, one of the superstars at the Warhol factory. We published a glamorous photo taken by Diane Arbus for Vogue. But, as the lead photo for the article, we had another Arbus shot of her nude, unkempt, and surrounded by bottles of alcohol, cigarettes, and drugs everywhere. There was this big outrage. People wanted me fired. Of course, I wasn’t fired. Tom Wolfe said the article was “too good not to print.”

For several years, Barbara was the Senior Editor at Harper’s Bazaar. She wrote for it and did a lot of editing for it. There was a huge amount of work to be done every issue, and there was that big deadline looming all the time.

“I began to think, what am I doing? Do I really want to make a career out of being an editor? I am re-writing everybody. What about my writing? I decided to give notice, and I did. I quit to write.”

And so, in 1973, shocked at how some people in the art world treated artists, Goldsmith embarked upon writing her first book, a work of fiction called The Straw Man. It was about a mythical billionaire who in his will left his vast collection to a museum in New York City that would house it in a new wing he would pay to have built. It was a work of fiction, but real people recognized themselves in it. The plot involved this billionaire’s son who, feeling he was short changed in the will after the rich old man died, tries to have the will overturned. It shot straight up to #2 on The New York Times Best Seller List.

“After it came out, I met with Henry Gelzheizer who said ‘I knew a lead character was me, but I would never answer the door with my shirt off.’”

Another astonishing thing happened as a result of this book. Seven weeks after The Straw Man was published, she attended the dedication of a new wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to house the art collection of the late Robert Lehman, who had willed it to the museum.

“Tom Hoving, the then-Director of the Met, rose and began to speak about Mr. Lehman and his great gift, not only for the artworks but for the wing to house it in, and I am listening to this speech, and I suddenly realize it is virtually identical to the speech I had written at the end of my book The Straw Man. In my speech, the Director extols how great the donor was. Had my book come after Mr. Hoving gave the speech, it could have been said I had stolen it from him, not the other way round.”

Barbara Goldsmith has, since that time, besides selling articles to The New Yorker and The New York Times, written five books, all works of nonfiction, all best-sellers. They are Little Gloria…Happy at Last, about the struggle for custody of Gloria Vanderbilt, from the time she was born until she was 10—made into a motion picture starring Bette Davis, Angela Lansbury, Christopher Plummer and Maureen Stapleton. The next was Johnson v. Johnson, about the longest and most expensive legal battle over a will in American history. The next was Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull, the remarkable story of Woodhull and other early feminists in the Gilded Age. And the latest is Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie, which has already been translated into more than 23 languages. She’s won many literary awards and has been the recipient of two Emmys.

And throughout all these times, she has been an active philanthropist in the City of New York, so much so that she’s counted as one of the 10 most prominent philanthropists in the city. She has been also named a “Living Landmark” by the New York Landmark Conservancy.

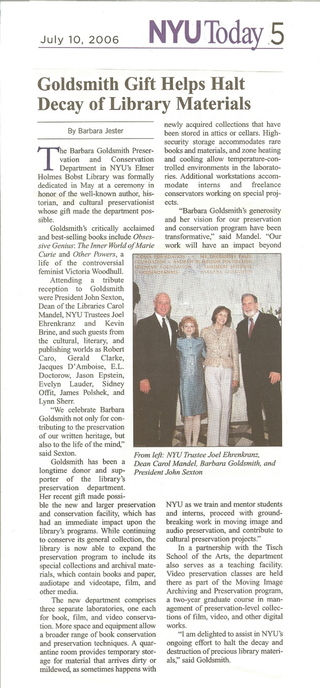

Barbara Goldsmith’s contributions have led to the Goldsmith Conservation and Preservation Laboratories at the New York Public Library, the creation of the preservation and conservation departments to New York University, to the founding of a state-of-the-art rare books library in the American Academy in Rome and another at her alma mater at Wellesley College. Also, she has created the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Awards, which annually focuses attention on imprisoned writers. She’s made 39 awards to imprisoned or missing writers. And after the awards were made, 34 were subsequently set free.

Perhaps her most extraordinary achievement, however, has been in the creation of an organization that sought to require that publishers print the first edition works of writers on cost-comparable, acid-free paper so these physical works would last 300 years instead of 30. In this attempt, with the signatures of 2,500 writers and about 60 publishing companies, she was able to secure a $20 million grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities for paper preservation and a law that all Federal documents must be printed on acid-free

paper.

Barbara Goldsmith lives today in Manhattan and in a 100-year-old house in Georgica. She was married to the late film director and writer Frank Perry. She keeps up with many friends and often sees her three children and six grandchildren.

New York Social Diary

By David Patrick Columbia

April 21, 2011

“Obsessive Genius”

I went down to Michael’s to lunch with Barbara Goldsmith. Michael’s was its Wednesday-jammed although Barbara and I quickly fell into an intense conversation about books, the state of the world, the President, the occult (she wrote “Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull”), and writing.

I’ve been a fan of Barbara’s since her book “Little Gloria Happy at Last” was published in the late 1970s. A page turner that you can’t turn fast enough, about the childhood of little Gloria Vanderbilt.

Since then I’ve also come to know her personally, and her interests and her generosity. Barbara is one of those people who quietly goes about living a very full life of philanthropy, work and literary activism while appearing to be stress-free. She “shares” her know-how and her talents, and does so as a matter of course.

She’s long been an active member and contributor to PEN where she endowed the PEN Freedom to Write Awards, given annually to spotlight writers imprisoned for expressing their views. Of the 37 writers imprisoned, missing or tortured at the time of her award, 34 set set free.

At the New York Public Library she funded the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation and Conservation Divisions while also organizing the country’s writers to be published on cost-comparable permanent paper (which last 300 years, instead of disintegrating in 30). She helped effect a $20 million annual increase in the budget of the National Endowment of the Humanities for paper preservation.

So when we do get together, the talk covers a lot of territory. Furthermore she travels often as well as dividing some her time between homes in Aspen and in East Hampton. She’s now reading “The Hare with Amber Eyes” which I recently finished, and finds it every bit as provocative, effecting and alarming as I did.

We talked about her most recent book, “Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie,” part of the Norton paperback series on lives of people in the sciences. The idea had been presented to her by her friend Robert Darnton a few years ago on behalf of Norton and their special series.

Madame Curie’s private papers had recently been released after 70 years under lock and key because their levels of radioactivity. The papers were considered too dangerous to handle for decades (something Madame Curie was unaware of in her work with the material – and which would eventually kill her). Time had dissipated the radiation and Barbara being the scholarly woman found the challenge fascinating.

The papers, notes, and letters turned out to be a treasure trove for the curious Barbara who is also a tireless researcher. She found the key to and the core of the woman who coined the term radioactivity, discovered polonium (which she named for her native Poland) and radium. She won two Nobel prizes, was the first female professor at the University of Paris and the first woman to be entombed on her own merits in the Paris Pantheon, after a rich and emotionally full life.

The finished work, “Obsessive Genius,” was published in October 2005. Because it was part of a rather scholarly series in paperback, there were no special expectations in terms of sales. But: it became a New York Times bestseller, has been published in 23 languages and sold out of its printings. Even more surprising to Barbara who has also written screenplays in the past, is that the book will be adapted and presented in a partnership between HBO and Sony with Barbara as co-producer.

BARBARA GOLDSMITH RECEIVED THE LITERACY PARTNERS LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD ON MAY 6, 2009 AT LINCOLN CENTER'S NEW YORK STATE THEATER.

Barbara Goldsmith was named a "Living Landmark" by the New York’s Landmark Conservancy and its affiliates! This prestigious honor was celebrated on November 5th, 2008

Barbara Goldsmith is a noted author, historian. Her best-selling books include The Straw Man, Little Gloria…Happy at Last, Johnson v. Johnson, and Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull (soon to be a major motion picture produced by Kathleen Kennedy for Universal Studios) and Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie. She is the recipient of many literary awards and two Emmy Awards for her work. Barbara Goldsmith has long been at the forefront of the effort to preserve our written heritage. She is the donor of the Goldsmith Conservation and Preservation Laboratories at the New York Public Library, and these Divisions were recently named in her honor. She has donated the Preservation and Conservation Departments to New York University as well as a state-of-the-art Rare Book Library at the American Academy in Rome and at Wellesley College.

Ms. Goldsmith accomplished the Herculean task of organizing this country’s most influential writers to insist that they be published on cost-comparable permanent paper (which lasts 300 years instead of deteriorating in 30.) She spearheaded a landmark event in which forty of the nation's most influential trade-book publishers and 2,500 writers signed a Declaration that they would publish only on permanent paper, thus insuring our cultural heritage and potentially saving billions of future dollars that might otherwise be spent on preservation. Ms. Goldsmith helped effect a $20 million annual increase in the budget of the National Endowment of the Humanities for paper preservation.

Barbara Goldsmith is dedicated to working for human rights and the freedom of expression. Nineteen years ago, she conceived the “PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Awards,” that consistently turns the media spotlight on imprisoned writers invariably securing their release. Of the 31 writers imprisoned or missing at the time of her awards, 28 were subsequently set free.

Barbara Goldsmith has written for The New York Times, Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. Ms. Goldsmith is a Doctor of Literature and of Humane Letters, honoris causa. Among her honors are an appointment to the President’s Commission for the Celebration of Women in American History, the Lifetime Achievement Award in the Literary Arts of the Guild Hall Academy of the Arts, the Poets and Writers “Writers for Writers” award, and the American Publishers Association Literary Award. She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Council on Foreign Relations.

Ms. Goldsmith served on the New York State Council on the Arts, the Commission for Preservation and Access and the Permanent Paper Task Force of the National Library of Medicine. She is a Trustee of the American Academy in Rome, the New York Public Library and was elected a Literary Lion at that institution. Barbara Goldsmith is a member of the Authors League, Authors Guild of America, and Poets & Writers. She was a founder of the National Dance Institute and wrote "Jump! Why Do I Dance?” which was performed at the White House. Information on her books follows.

Barbara Goldsmith was at the forefront of the effort to preserve our written heritage. She helped accomplish the Herculean task of organizing this country’s most influential writers to insist that they be published on cost-comparable permanent paper (which lasts 300 years instead of disintegrating in 30) and spearheaded a landmark event in which forty of the nation's most influential trade-book publishers and 2,500 writers signed a Declaration that they would use only permanent paper, thus insuring our cultural heritage. Ms. Goldsmith has often testified before the congressional committees on the importance of writer’s grants and on the preservation of our written heritage. She helped effect a $20 million annual increase in the budget of the National Endowment of the Humanities for paper preservation. Goldsmith is dedicated to working for human rights and the freedom of expression. Eighteen years ago she conceived the “Barbara Goldsmith/PEN Freedom to Write Awards,” that consistently turn the media spotlight on writers imprisoned for expressing their views and has invariably seen them released. Of the thirty-four writers imprisoned, missing, or tortured at the time of her award, thirty-one were soon set free.

A Testament of Riches Shared

By Pamela Ryckman

The Financial Times

September 28, 2007

Perched 17 floors above Park Avenue, with the traffic barely audible through an open window, Barbara Goldsmith is surrounded by friends. Louise Nevelson and Andy Warhol greet guests beside the door, while in the living-room Stone Roberts mingles easily with Roy Lichtenstein, Donald Sultan, Brian Hunt and Jim Dine. The bestselling author and philanthropist began her career writing about art for Harper’s Bazaar and New York magazines and she has known them all.

On the day we meet, Goldsmith serves lemon cake with sparkling water on a silver tray before turning to the books that run floor-to-ceiling along her dining room walls. The one on the top shelf with the purple jacket is Little Gloria . . . Happy at Last, her 1980 bestseller about the custody battle over Gloria Vanderbilt, which became a television mini-series for which Goldsmith won two Emmys. And there’s Johnson v. Johnson, her story of the court battle surrounding J. Seward Johnson’s $500m will, and her novel The Straw Man.

Goldsmith’s dog Vicky emerges for a nuzzle, and guests learn that she is named for the heroine in Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull, which occupies a shelf near copies of her recent hit, Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie, for which she won the 2006 Science Writing Award.

In spite of her books’ robust reviews and runaway sales, Goldsmith is renowned as much for her philanthropy as for her voc ation.

“I want to be known as a writer, not as a philanthropist,” she says, fingering her chunky jade necklace. “I’ve been extremely lucky and I take the responsibility of philanthropy as a given, but writing is my profession.”

Standing in her sun-soaked eyrie, one realises that Goldsmith’s more than five decades as an author and historian inform every aspect of her life, including her charitable giving. Her philanthropy is the result of the same intellectual curiosity and compassion that fuels her writing, and her causes are a natural outgrowth of her professional obsessions.

“Don’t things just come up?” she demurs, before explaining how she became devoted to book conservation. “When I was researching Little Gloria, I would see documents from before 1850 that were in fine condition, and then there were more recent ones I could barely get to the copy machine before they fell apart. I wanted to know why.”

Goldsmith learnt that paper was disintegrating after 30 years owing to high acidity levels in post-Industrial Revolution production processes, and that comparable acid-free paper lasting 300 years could be found for the same price. “It just seemed so clear what we should do.”

Back to the bookshelves: Goldsmith beams in a photo from 1989. She’s standing with Kurt Vonnegut, Barbara Taylor Bradford and others, holding the Declaration of Book Preservation. A zealous Goldsmith galvanised 40 of the most influential trade-book publishers and 2,500 writers to publish only on permanent paper, and eventually secured a $20m annual increase in the federal government’s budget for paper preservation.

These changes will save millions of dollars in future conservation costs and, she hopes, prevent our literary heritage from “dropping down the Orwellian memory hole”.

Similarly, Goldsmith created the Freedom to Write Award because she saw something wrong and wanted to fix it. She was working with PEN, the international association of writers, and learnt of authors disappearing, or being tortured and killed. “I just thought if we could turn a major media spotlight on these issues, then governments would be unable to ignore them,” she says. The night before we met, Goldsmith received word that Normando Hernández González was being taken from his prison cell to the hospital.

Hernández González, a dissident writer and critically ill Cuban prisoner of conscience, is honoured this year and, if released, will join the 30 of 33 imprisoned writers to be liberated over the past 20 years because of media attention resulting from the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award.

In philanthropy, as with most things, Goldsmith’s advice is to follow your passions.

“We live in a world where you can’t support everything, so you have to think about what’s closest to your heart. I’m at the point where I have staked my territory and I want to do the best job I can and still have a writing life,” Goldsmith says of concentrating her charitable works, which include acting as a trustee for the New York Public Library and the American Academy in Rome.

One must prioritise because, according to Goldsmith, philanthropy done correctly requires not only money, but also time and expertise. Taking a tip from her friend and mentor, the late Brooke Astor, Goldsmith says it’s important to remain intimately involved with the institutions you support.

“I don’t respond well to re active philanthropy. I don’t want to give money to an organisation if I don’t know how it’s being spent,” she says.

This means ensuring funds go directly to the cause, not to administration or to self-congratulatory flourishes. Goldsmith was quick to end her association with a woman who boasted that her philanthropy office, which had been decorated by a top designer, was “so much more chic than that plain place Brooke Astor worked out of”.

She admiringly quotes Liz Smith, the gossip columnist and honorary chairman of Literacy Partners, a non-profit organisation: “There will be no goody bags because every cent donated goes right to the work, so you’ll have nothing to give away to others, who probably don’t want it either,” Goldsmith recalls her saying at a dinner.

These days, Goldsmith laments, few people seem to understand the importance of giving wisely, or giving at all. “I grew up in an extremely philanthropic family. I was trained to give back,” she says, recalling her father as “a real Horatio Alger story”, a man who rose from selling pretzels on Coney Island to become chairman of Pepsi-Cola. “Very few people today understand the quid pro quo, that if you make a billion dollars, you should donate a hospital.”

She mentions that in the Bible, Maimonides’ highest form of charity is anonymous giving. So why, then, the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award, or the Barbara Goldsmith Reading Room at the American Academy in Rome, or the Goldsmith Conservation and Preservation Laboratories at the New York Public Library, or the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation and Conservation Departments at New York University’s Bobst Library?

Goldsmith donates anonymously, too, and she’s aware that others exploit naming opportunities for “instant ancestry”. But sometimes she thinks strategic recognition has greater impact. “I put my name on places where it will attract more money and where my expertise might draw people to the cause,” she says.

A leitmotif in Goldsmith’s writing has been the discrepancy between image and reality, and in the past she has been critical of society’s cult of celebrity; in her 1983 essay The Meaning of Celebrity, she denigrates the use of philanthropy as a publicity stunt.

But Goldsmith is pragmatic enough to understand exploiting fame for good. It was she, after all, who persuaded Norman Mailer and Kurt Vonnegut to help rally Congress for acid-free paper. And it was Goldsmith who, at the request of the former First Lady, first covered the Betty Ford Clinic.

“The First Lady told me she’d been a drunk and she’d needed an intervention and she’d had a breast removed, and she said: ‘I want you to take all that and use my celebrity to put my clinic on the map.’ She was very realistic and she understood society.”

So it’s not surprising now to see Oprah Winfrey’s endeavours in Africa, or Bono sandwiched between Bill and Melinda Gates on the cover of Time magazine. “They’re using celebrity in a positive way.”

Goldsmith has achieved a certain celebrity herself, yet she doesn’t want to write a memoir and she doesn’t care about legacy. “I just want this trip to be as good as I can make it,” she says.

Down a long hall, past bedrooms and an office lined with diplomas and distinctions, is the room where Goldsmith writes. Here she is again, surrounded by friends.

“Here’s me and Clark Gable, me and Cary Grant. Of course my grandchildren ask, ‘Who are they?’ And there’s Jacques D’Amboise, there’s my editor Bob Gottlieb, and here’s the opening of the Brooke Russell Astor reading room, and here’s one with the Literary Lions, and here’s me and Mailer with our medals, me and Tennessee Williams, and here’s Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese.”

On the next wall hangs a striking print of homeless people under the IBM building, signed “un hommage” to Goldsmith by Henri Cartier-Bresson, and a picture of “Sylvette”, the sculpture she persuaded Picasso to donate to New York University, near the photo of Goldsmith taken by Andy Warhol. Snapshots of Goldsmith’s three children and six grandchildren sit alongside photographs of the Clintons. “They’re all personal,” she smiles.

Like it or not, intended or not, Goldsmith is leaving a legacy – one of art, literature, friends, family and philanthropy. A history still in the making.

BARBARA GOLDSMITH to Received Authors Guild 2007

Distinguished Service Award Presented by ROBERT CARO

ANDY BOROWITZ Hosted

New York, NY, April 2007 – Comedian and satirist Andy Borowitz, author of the popular free online "The Borowitz Report," will be Master of Ceremonies of the 15th Annual Dinner in celebration of writers and writing to benefit the Authors Guild Foundation and the Authors League Fund on Monday, May 21st at the Metropolitan Club in New York City. This year the Authors Guild will honor author and historian Barbara Goldsmith with its Distinguished Service Award presented by the eminent biographer

Robert Caro. Barbara Goldsmith's acclaimed best-selling books and articles have won her numerous prestigious awards, among them the U.S. Presidential Citation, election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Presidential Commission for Preservation and Conservation, two Emmy's, New York Public Library's Literary Lion Award and New York University's Distinguished Writing Award. She is the recipient of four doctorates, honoris causa. Her most recent book, Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie, has been translated into fifteen languages and just earned her The American Institute of Physics' highest honor for a writer, its 2006 Science Writing Award.

In the New York Times Vartan Gregorian, President of the Carnegie Corporation, cited Barbara Goldsmith as one of the ten most enlightened and influential philanthropists in America. She originated and spearheaded a successful campaign culminating in a 20 million dollar contribution from the Federal Government to convert to acid-free permanent paper, thus helping preserve our literary heritage for 300 years and saving untold millions in future conservation costs. She is a major donor of Preservation and Conservation facilities at several prestigious institutions here and abroad. She originated the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Awards and harnessed world-wide media to spotlight the terrors and humiliations faced by writers of conscience. Of the 32 writers imprisoned at the time of her awards, 30 were subsequently released.

The Co-chairs of the evening are authors Judy Blume, Barbara Taylor Bradford and Robert Bradford, Sandra Brown, Mary Higgins Clark, Michael Crichton, James Gleick, John Grisham, A.E. Hotchner, Garrison Keillor, Joanne Leedom-Ackerman, John R. MacArthur, Katherine Neville, Mary Pope Osborne, R.L. Stine and Jane Stine, Scott Turow and Stuart Woods.

Confirmed attendees included: Ken Auletta, Roy Blount, Patricia Bosworth, Barbara Taylor Bradford, Sandra Brown, Robert Caro, Carol Higgins Clark, Mary Higgins Clark, David Patrick Columbia, Gael Greene, John Grisham, Robie Harris, A.E. Hotchner, Susan Isaacs, John R. MacArthur, Katherine Neville, Victor and Anne Navasky, Sidney Offit, Mary Pope Osborne, Hannah Pakula, Peter Petre, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Peter Price (President of the National Television Academy), Roxana Robinson, Lynn Sherr, James Stevenson, Jean Strouse, Nick Taylor, Jeffrey Toobin, Amanda Urban, Scott Turow, Margo Viscusi and Stuart Woods.

All the profits from the event will support the Authors Guild Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting writing as a livelihood and promoting the importance of writing, publishing, copyrights, free speech as well as the Authors League Fund, which helps professional writers and dramatists who find themselves in financial need because of medical or health related problems, temporary loss of income, or other misfortune.

The evening will begin with cocktails at 6:30 p.m. followed by dinner and the award presentation at 7:30 p.m. Tickets can be purchased by calling 212-594-7931.

On January 7th, 2007 Barbara Goldsmith was informed that she had just earned The American Institute of Physics' (and its 13 affiliated organizations) highest honor for a writer, its Science Writing Award for "Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie".

Aspen Magazine, Summer 2005

Views Ideas

Leading the Way

by Daniel Shaw

In July, a diverse group of world luminaries comes to the Aspen Institute's Aspen Ideas Festival. Among them is historian BARBARA GOLDSMITH, who is leading a talk on women and leadership. DANIEL SHAW tells us why she is the right woman for the job.

In 1987, Barbara Goldsmith had a really good idea. An executive-committee member of the PEN American Center and one of America's foremost journalists and social historians, she created and began underwriting an award to spotlight dissident writers enduring persecution under oppressive regimes. To date, 28 of those recipients have been released from prison within four months of receiving the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Awards. "Governments cannot resist newspapers all over the world telling them to let these people out," Goldsmith says.

That initiative and its profound impact alone would have rendered Goldsmith worthy of inclusion in the Aspen Institute's inaugural Aspen Ideas Festival, July 5-10. In this conference, also presented by "The Atlantic" magazine, Goldsmith and ABC news and 20/20 correspondent Lynn Sherr are moderating a tutorial on women and leadership. And Goldsmith can't wait. "I think it's a wonderful gathering of people from totally different disciplines," she says. "They're mixing it up like you can't believe."

Mixing it up is something the Aspen Institute is determined to do. With the goal of creating "an exciting, unique opportunity for a broad and diverse group of participants to engage in intellectual activities," the Institute is presenting tutorials, seminars, and conversations on topics such as global economics, health and bioscience, culture and society, leadership and the state of the environment. Attendees include Amazon.com founder and CEO Jeff Bezos, Human Genome Sciences founder William Haseltine, MSNBC host Chris Matthews, Nobel Prize-winner Toni Morrison, United Nations under-secretary-general and special representative Olara Otunnu, Harvard University president Lawrence Summers, and "U.S. News and World Report" editor in chief Mortimer Zuckerman.

As a founding committee member of the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, Goldsmith has seen firsthand the benefits of bringing different fields of knowledge to one setting. "It's amazing how an economist can learn from an artist," she says. Yet in many ways, the Aspen Ideas Festival is a celebration of individualism-- after all, a groundswell of ideas starts with one person. "People say individuals cannot make a difference, but I agree with Margaret Mead, who said, 'Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed individuals can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has," says Goldsmith. The festival, she notes, comes at a critical juncture for America: We now have the technology, power, and money to implement ideas in ways never before possible.

If there is a common thread linking Ideas Festival participants, it is the undeniable influence each of them-- from Colin Powell to Jane Goodall-- has had on our society and the way we view and live in the world. As a journalist, social commentator, and historian, Goldsmith has done her share with the writing. From "Little Gloria . . . Happy at Last", which tells the story of the custody battle over Gloria Vanderbilt, to her latest offering, "Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie", her books have been best-sellers. She manages to popularize history-- to bring it alive-- without sacrificing substance. "Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull" is on its way to becoming a major movie, and her articles for "The New Yorker" and other magazine always offer a fresh take on our culture.

While her vivid accounts have moved, entertained, and informed millions, her myriad philanthropic and volunteer efforts to promote and protect human rights have directly affected lives worldwide. The New York Public Library, where she is an executive-committee member, named its Barbara Goldsmith Conservation and Preservation Divisions after she came up with another inspired idea. Goldsmith, an elected member of the American Academy for Arts & Sciences, became increasingly concerned that our era's books were surviving only about 30 years-- as opposed to the 300 years they'd lasted before the industrial revolution changed the publishing process from acid-free paper to acidic paper. She organized the most influential writers of our time to launch a campaign for the more permanent acid-free paper, and they won a $20 million governmental grant to make it happen.

In 1989, Goldsmith received a signed declaration from Congress and commitments from every major publisher in the nation and 2,500 writers-- all agreeing to use only acid-free paper.

"Now, that was a great idea," she says without a trace of boasting. "Anybody can have a great idea if they go for it. You have to play up great ideas, and I believe this conference will. Marie Curie was a genius. I'm no genius, but I've had a few good ideas."

An Author With a Passion for Philanthropy

Lunch at the Four Seasons

THE NEW YORK SUN

BY PRANAY GUPTE

February 21, 2006

Barbara Goldsmith says she was born to share.

"It was inculcated in me early that if you were privileged, then you're obliged to give back to society," the author of best sellers and historian said yesterday."My parents made it clear to my sister Ann and me that it was important to think about other people, and not just yourself."

She took their exhortation seriously. Almost as much as her notable books - "Little Gloria ... Happy at Last," "Johnson v. Johnson," "Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie," and "Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull" - are celebrated, Ms. Goldsmith is herself celebrated for her philanthropy.

"I believe in saving people and saving books," she said.

The people she "saves" are involved with books. Nearly 20 years ago, Ms. Goldsmith conceived the "PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Awards."They help focus attention on imprisoned writers. Of the 37 writers imprisoned or missing at the time of her awards, 34 were subsequently set free.

The books that Ms. Goldsmith "saves" are to be found in myriad places, including the Goldsmith Conservation and Preservation Laboratories at the New York Public Library. She also has donated the preservation and conservation departments to New York University, and she has gifted a state-of-the-art rare-books library to the American Academy in Rome and another one to her alma mater, Wellesley College.

Ask her to elaborate on her philanthropy, and Ms. Goldsmith demurs.

"I've been very fortunate to find the trip joyful - full of love and good work," she said. "What more could one ask?"

One could, of course, ask her about the wellspring of her sensibility. The response is to be anticipated: her parents.

Ms. Goldsmith's father, Joseph I. Lubin, was born as the youngest of eight children in a Lower East Side tenement. He established himself as an accountant and lawyer, rising to become board chairman of Pepsi-Cola at 40. He endowed Pace University's Lubin School of Business and Yeshiva University's Albert Einstein College of Medicine.Along with John D. Rockefeller II, he donated millions for the purchase of stockyards along the East River in 1946 so a headquarters for the United Nations could be built.

"His was an authentic rags-to-riches story," Ms. Goldsmith said.

Her mother hailed from more fortunate circumstances than Lubin. Evelyn Cronson's father, Reuben, was chief of surgery at New York's Presbyterian Hospital. Active in social work, Evelyn helped retarded children; during World War II, she prepared bandages for troops - and she taught her younger daughter the technique.

"She also taught me how important it was to have a happy family life," Ms. Goldsmith said."She would say,'Be careful - you don't want a scrapbook full of honors, but no life.' One of my mother's regrets was that her father, a doctor, never let her be a doctor herself."

That would have been one of the few regrets in an otherwise fulfilling life. Evelyn Cronson Lubin lived to see Barbara Goldsmith develop into an acclaimed writer - one of the most successful practitioners of what came to be called "The New Journalism" - and an Emmy-winning documentary maker.

She lived to see Ms.Goldsmith's three adult children - Alice, John, and Andrew - get married and have children.

She did not live to see Ms. Goldsmith's six grandchildren. Neither did she live to see her daughter organize 2,500 of America's most influential writers to insist that they be published on cost-comparable permanent paper, which lasts 300 years instead of deteriorating in 30. Ms. Goldsmith secured a $20 million grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities for paper preservation.

"This will potentially save billions of future dollars that might otherwise be spent on preservation," Ms. Goldsmith said.

Her work on technical and business matters relating to publishing might suggest that Ms. Goldsmith had commerce in her DNA.

Not so, she said.

"No business was ever discussed in our house," Ms. Goldsmith said. "What was discussed was history.We were given quizzes at the dining table. My father was an American-history buff. We had a large library. I read everything that I could get my hands on - Dumas, Thackeray, Proust, Dickens."

It was quite possibly such reading that spawned in her a desire to write. When she was nine, Ms. Goldsmith created a character named Jackson the Jester, and she read her composition aloud before her class at Mayflower Grammar School in New Rochelle. When she finished, she noticed that several of her fellow students were cry ing because of the pathos in the story.

"That was a 10-minute recitation - 10 minutes that changed my life," Ms. Goldsmith said.

She vowed to become a writer. While she was at high school,she worked summers for Town & Country magazine. Later, she worked for the New Yorker. She gained early notice for her profiles of Cary Grant, Audrey Hepburn, Danny Kaye, and Deborah Kerr. Ms. Goldsmith also interviewed and wrote about Picasso, Marcel Breuer, and I.M. Pei, among other artists and architects.

"I've always been curious - I like to peel the onion," Ms. Goldsmith said. "If something doesn't make sense, then you don't take it at face value," she said.

That could well be a tutorial for today's crop of young writers. But Ms. Goldsmith said the term "The New Journalism" is a misnomer.

"There's good journalism and bad - that's it," she said.

What she frets about is that there isn't enough of the observation, detail, intuitiveness, and understanding of people in much of today's reporting and writing.

"And where has the passion gone?" she asked. "It's so important to have a sense of adventure."

A reporter, who recalled reading her magazine profiles and early books as a young man, asked Ms. Goldsmith how she saw her extraordinary life in the privacy of her mind.

She replied: "The joy has been in the doing."

Saving Books from the

Paper They're Printed On

By Eleanor Blau

The New York Times

"It started out as an avocation, and it became really an obsession."

Barbara Goldsmith, an author and social historian, was speaking of her 15-year crusade against acidic paper, a self-destructive menace to the written word that has caused millions of books to crumble to dust.

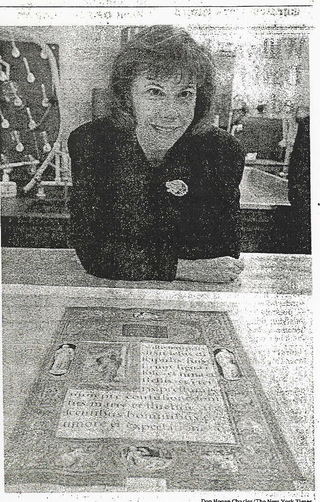

Ms. Goldsmith, a trustee of the New York Public Library, endowed the lab where the library preserves its wares, saving many volumes on microfilm and using scientific alchemy to slow the deterioration of a special few.

But her efforts have reached far beyond the library here.

"I think she put the issue squarely on the map," said Paul LeClerc, the president of the New York Public Library. She led "a turnaround both within the publishing community and the Federal Government," he said, "a movement away from paper that ultimately disintegrates and toward a paper that is going to be around for hundreds of years."

Hardcover trade books are now routinely printed on acid-free paper, and Federal agencies are required to use permanent paper for publications of "enduring value." But the growing movement to recycle paper could reverse the acid-free successes, since recycling some kinds of paper requires the use of acid. So Ms. Goldsmith is still at work.

She dates her obsession to 1979, when she was doing research for "Little Gloria . . . Happy at Last," her best seller about the custody struggle for Gloria Vanderbilt. "I couldn't understand why some old documents were in wonderful condition and others I couldn't even get to the Xerox machine before they turned to dust," she recalled.

The problem, she learned, was immense: millions of books and periodicals published since the 1850's-- filling more than 30 miles of shelves in the New York library alone-- were disintegrating. Their pages were made of wood pulp, a type of paper developed in the 1850's when paper made from cotton rag and linen rag became scarce. Unfortunately, lignin in wood pulp oxidizes and turns brown. A chemical added to keep ink from feathering-- alum-rosin sizing-- also discolors the paper. And the matter grows worse over time as the alum combines with sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere.

American librarians were not generally aware that the paper was falling apart rapidly until the 1950's, when William J. Barrow, an archivist, sounded the alarm. By 1960, he had helped create a wood-pulp process using alkaline chemicals. But 20 years later, most mills were still making acidic paper.

"What had happened was that the American Library Association, every preservation department, all knew about this and it came up at every conference," Ms. Goldsmith said. "It was the converted preaching to the converted." When she asked one library official why no one had spread the word, she recalled, he said: "'This is not a sexy issue. It's such a dry issue.' I said, 'No, it's not!' I was just on fire with it."

She still sounds on fire with it. Ms. Goldsmith, who has degrees from Wellesley College (1953) and Columbia University (1957), and whose works include "Johnson v. Johnson" (1987), about the contested will of the heir to the pharmaceutical fortune, once said she wrote books out of a passion to "see that our society straightens out." Her passion for the acid-free paper crusade was evident as she recounted her early efforts during an interview in her Park Avenue apartment.

"It didn't go very fast at first because I was out there sort of by myself and nobody believed it," she said.

But by 1989, she was able to gather dozens of authors and publishers at the library to declare that form now on they would use only acid-free paper, if available, "for all first printings of quality hardcover trade books in order to preserve the printed word and safeguard out cultural heritage for future generations."

Ms. Goldsmith went to Washington with writers who included Kurt Vonnegut Jr. "We were very successful in getting legislation that all Governmental printing of any quality would be done on acid-free paper," she said. "Then it was sort of like a house of cards because that gave a lot of the mills enormous incentive to convert to acid-free paper."

Another incentive was the price of wood pulp, which rose in the mid-1980's, encouraging American mills to substitute calcium carbonate-- something that had been done in Europe a decade earlier, Ms Goldsmith said.

These days, about 75 percent of fine paper (not including newsprint) used for printing and writing in the United States is alkaline, said Ellen McCrady, the president of Abbey Publications, which issues newsletters about paper. In 1985 the figure was about 25 percent.

Ms. Goldsmith's next goal is to educate recyclers about the acid-paper problem; in May there will be a conference at the library dedicated to that issue. Ms. Goldsmith said she thought many recyclers did not understand that the acid they sometimes add in recycling pollutes.

"They think they're doing something wonderful, they're saving the forests," she said. "But it's a Catch-22, because if you're not cutting down trees but you're polluting the streams and air, you don't want to do that, either."

While the crusade continues, the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation Laboratory pursues its work deep in the library's basement, where bouldered walls reveal remnants of the reservoir that stood on the site more than a century ago.

She endowed the lab in 1988 with $1 million from a foundation that bears her name-- money inherited from her father, Joseph I. Lubin, the son of a poor immigrant family who went on to become board chairman of the Pepsi-Cola Company. Since then, the lab has received two Federal grants of $2 million each. Most of its work consists of microfilming.

"I'm not against microfilming," Ms. Goldsmith mused. "It's just that I don't want the book to become an artifact. I don't want to put my grandchild on my knee and read her 'Wind in the Willows' at some computer screen."

BARBARA GOLDSMITH'S TELEVISION APPEARANCE ON

CONNIE MARTINSON TALKS BOOKS

Barbara Goldsmith has written "Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie"(Norton $23.95). It is part of the James Atlas series entitled "Great Discoveries". Despite the limits of book size, 233 pages, it is a superb book that makes Marie Curie, the first woman to be awarded two Nobel prizes, come alive.

She was born in Warsaw in 1867 where her name was Marya Sklodowski. Her father was a Professor who took over the raising of his children, four daughters and a son, when her mother, Bronislava, who was ill for many years, died in 1878. Marya was always the student with the intent to go to Paris and study at the Sorbonne, but first it was her elder sister Bronya's turn to go to Paris. During that time, Marya worked as a governess for a well to do family. The family did not consider her background good enough to marry their son. She was heartbroken and determined never to fall in love again.

In 1891, Marya became Marie when she moved to Paris and began her studies at the Sorbonne. She was first in the science exam and took a second in mathematics. It was then that she met the man who would be the key to her experiments , discoveries, and her love, Pierre Curie. Pierre and his brother, Jacques, had discovered the electrical charge generated by a piezoelectric quartz which today is seen in sonar, ultrasound, mobile phones, etc. Pierre was as unique as Marie, it was as if they were two pieces of a puzzle that completed the other. They were married on July 26, 1895.

Marie continued her work on the magnetic properties of steel which would win the Gegner Prize from the Academy of Sciences. In 1897 she gave birth to her daughter, Irene, who would also win a Nobel Prize in 1935 for her work in artificial radioactivity.

Barbara Goldsmith was given unlimited access to the Curie papers by the grand daughter, Helene Langevin-Joliot. Goldsmith has made the Curie scientific discoveries understandable to the lay person. Marie becomes a breathing human who could be jealous that Gerhard Carl Schmidt beat the Curies by three weeks in publishing his findings on the radioactivity of thorium. It made her even more determined to discover a new element. Her first was "Polonium" and her second was "Radium".

In November 1903. the Curies received the notice that they had won the Nobel Prize. They did not attend as Marie was suffering from the death of her father and a miscarriage. Throughout her life, Marie, in her obsessive behavior, would take to her bed in a depressive state. In 1905, her daughter, Eve, was born.

Radium became the hot new asset to commercial use , everything from health tonics to teeth whitener to that day's answer to viagra. The family could afford to take vacations. Pierre was a member of the Scientific Academy. But Radium was taking its physical payment from Pierre with his bone deterioration that caused him to fall in the street as he was pushed down by a run away horse. He slipped and the wagon ran over him and crushed his skull. He was forty-nine. And for Marie, her world collapsed. She could give his lectures but there was no light in her world for five years.

In 1910 she became involved with a younger married scientist, Paul Langevin, whose wife eked out the ultimate revenge by publishing Marie's love letters to Paul. Because of this disgrace, the Nobel Prize was awarded to her but they asked her not to attend. It goes without saying that Marie was the victim of female discrimination throughout her life. She also refutes the inane announcements by the president of Harvard concerning women and the sciences. This book is a "must" for gift giving, easy to read, informative on scientific discoveries and human in the story of one woman's life.

Praise for Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie

"History has treated Marie Curie as a mysterious genius, as if she sprang full-blown from the head of Zeus—or perhaps her husband. Barbara Goldsmith gives us a flesh-and-blood woman whose life and work will inspire our own. Marie Curie was the brilliant discoverer of radium and the radioactivity crucial to modern science. Barbara Goldsmith is the brilliant discoverer of Marie Curie."

-- Gloria Steinem

“Barbara Goldsmith has done the near impossible in “Obsessive Genius”, her remarkably moving and surprising biography of Madame Curie. She never loses the Luddite reader like me in a hopeless morass of scientific details. Instead, she makes the scientific information sparkle with the same clarity that matches her telling the accomplishments and strange celebrity of the woman who founded modern radioactivity. Goldsmith makes me understand the very foundations of modern science in a way I never have before. This is a book to buy for yourself and then buy ten more copies to give as presents to grateful friends.”

-- John Guare

“Great lives in science are all about passion and curiosity. Marie Curie, the Polish-born discoverer of radium, had both in grand measure. But down the road she helped open-up nuclear energy, which meant atomic bombs, and put Curie center stage during one of the great turning points in scientific history. Barbara Goldsmith has uniquely captured the woman and her science.”

-- Thomas Powers, author of Heisenberg’s War

“An uncommonly heartfelt and empathic profile of a scientific hero.”

-- Timothy Ferris, author of, Coming of Age

in the Milky Way and Seeing in the Dark

“Barbara Goldsmith has written a superb study of a fascinating and historically important woman whose life is a great deal more interesting than the myth it inspired. Obsessive Genius is an obsessive read.”

-- Gay Talese

“Obsessive Genius vividly portrays the powerful personal story of privation, sacrifice, triumph, and reward of one of the greatest scientists of the Twentieth Century, Marie Curie. It is a fast-paced exciting tale of scientific adventure which I read in one sitting. Barbara Goldsmith makes an important addition to her growing body of work on the life and accomplishments of women who have shaped our history and our lives.”

-- Dr. William Haseltine, Ph.D., Chairman and CEO, Human Genome Sciences, Inc.

Praise for Johnson v. Johnson

"EPIC TRAGEDY, intertwined with the themes of sex, money, and domination-along with incest, drug addition, suicide, attempted murder, and betrayal as juicy side dishes." - Liz Smith

"Fascinating . . . A story of betrayal, disappointment, avarice, and revenge." - San Francisco Chronicle

"Captures all the drama and farce of the longest and probably the costliest will contest in U.S. history." - The Wall Street Journal

"A pornographic true-life soap opera of stupefying proportions! Barbara Goldsmith is a peerless social chronicler of the high and-in her hands-the often not so mighty." - Peter Maas

"A classic portrait of greed and betrayal." - Patricia Bosworth

"A dramatic account of the sensational legal contest and, even more engrossing, of the strange and sometimes outlandish personalities on each side of the case." - Parade Magazine

The mini-series based on Little Gloria . . . Happy At Last

From imdb.com: The Internet Movie Database

Little Gloria…Happy at Last (1982) (TV)

Directed by: Waris Hussein

Writing credits: Barbara Goldsmith (book)and William Hanley

Honors: Two Emmy Awards

Genre: Drama

User Comments ABSORBING DRAMA!

"Beautifully made adaptation of Barbara Goldsmith’s Best-seller book, about the sensational custody battle of 10 year old Gloria Vanderbilt, that took place in 1934. Great cast, with Angela Lansbury and Bette Davis taking the acting honors. Detailed and very real, with a nice period flavor. This is a true but ultimately sad story. One of the best TV mini-series ever made."

Cast overview (first billed only)

Martin Balsam......Nathan Burkan

Bette Davis......…Alice Gwynne Vanderbilt

Michael Gross:......Gilchrist

Lucy Gutteridge:......Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt

John Hillerman:......Maury Paul

Barnard Hughes:......Justice John Francis Carew

Glynis Johns:......Laura Fitzpatrick Morgan

Angela Lansbury:......Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney

Rosalyn Landow:......Thelma Morgan Converse

Joseph Maher:......Smythe

Christopher Plummer:......Reggie Vanderbilt

Ken Pogue:......Judge James Aloycious

Maureen Stapleton:......Nurse Emma Kieslich

Leueen Willoughby:......Consuelo Morgan

Jennifer Dundas:......Little Gloria

Color: Color

Sound Mix: Mono

Praise for The Straw Man

“Barbara Goldsmith’s writing is crisp, clean, and flowing. An amazing, extraordinary work of stylish craftsmanship, The Straw Man gives modern novels a vitally needed vitamin injection and those who care about literature a cause for rejoicing.”

--New York Magazine

“Absolutely first-rate . . . an insightful, suspenseful tale.”

--George Plimpton

“Knowing, understanding . . . a witty oasis among recent fictions—if it is fiction.”

--Truman Capote

“Barbara Goldsmith’s got it right. Remarkably entertaining! Brilliant social criticism.”

--John Kenneth Galbraith, New York Magazine