An Ongoing Vision: Robert Wilson and The Watermill Center

An Ongoing Vision

by Barbara Goldsmith

The pulverized cement of what once had been a road crunched beneath my sandals. The dry scratchy weeds came up past my waist. The year was 1992. The June day was unusually hot. I wondered why Robert Wilson had insisted I come to this deserted, desolate place. In the distance was an assemblage of decaying buildings, what was left of an abandoned Western Union research facility situated on the edge of an Indian Reservation on Long Island. We stood for a time in silence. Finally, Wilson’s arm rose in a gesture that was slower than slow and ended as he turned his wrist and extended a finger, pointing at the peeling, rusting buildings. “Look,” he said, “See the light.” Then after another seemingly interminable pause, “It’s going to be perfect.” On that day we had different visions, I saw what was there. Robert Wilson saw what it was to become.

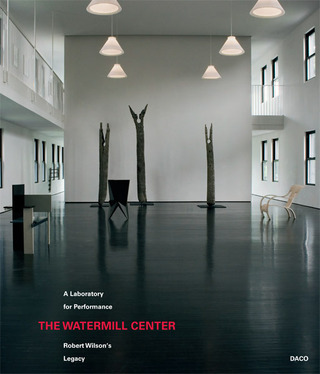

In less than two decades, the Watermill Center has emerged as a place of pristine, light-filled beauty and function. The weeds have been replaced with masses of carefully cultivated grasses and gardens. The main building houses 850 sculptures, photographs, paintings, holographs, drawings and furniture. There are performance spaces, artist’s and writer’s studios, art galleries, music rooms, dance rehearsal spaces, and residential facilities where interns and visitors create the art that Wilson sees everywhere as a life force.

Through an unprepossessing wood door under the main building one enters the Watermill Center’s storage space, and what space it is! This 130 by 12 foot room contains over 3,000 objects. It reminds one of Lord Carnarvon’s query to the archeologist Howard Carter on penetrating the heart of King Tut’s tomb. “Can you see anything?” asked the anxious Carnarvon, and Carter replied, “Yes, I see wonderful things.” This so-called storage space is a précis of Robert Wilson’s life and travels. A polymath, he has visited and worked in over forty countries and studied hundreds of cultures. Here objects are not organized by period or country but by the incredible eye that first became visible to me in the 1970’s when Wilson’s “Einstein on the Beach,” like Einstein himself, altered notions of time and space.

Robert Wilson sees the creation of art not only in a near priceless Tang dynasty statue still with its original paint but in a Japanese red and black lacquered cardboard mask he has placed next to it, one that costs no more than a candy bar. A collection of twenty staffs and spears from as many cultures are grouped together. These objects are juxtaposed so somehow their randomness is transformed to the precise, a statement about the nature of art itself in disparate cultures.

The storage space adjoins a modest library and study center. This area is in its infancy, a random compilation of books and periodicals that artists and scholars can consult, a room for an occasional lecture, and a nascent attempt to tie the humanities into the mission of the Watermill Center. One day Wilson, ever trying new forms that surprise the eye, asked the beleaguered librarian to place the books on the shelves in pyramid shapes, the tallest in the center sloping down so that they would look interesting. They did, until you tried to find the book you were looking for.

Once again, it isn’t what’s there, but a vision of what will be there. As Goethe once wrote, “Whatever you do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius and power and magic in it.” Now Robert Wilson solemnly unfurls plans for a unique and perfectly organized and catalogued library to take over this room and to occupy a newly-built wing with housing space for some 33,000 volumes to study past and present art, architecture, performance, opera, dance, theater and to cultivate an original vision of what the future will bring. These volumes will be gathered from almost eighty countries, because at the Watermill Center art speaks a universal language. The library of Robert Wilson’s vision, he explains, is somewhat similar to The King’s Library (now called The Enlightenment Gallery) housed in a tall glass tower at the British Library in London. It contains the collection of King George III and it is considered the most significant collection from the era of The Enlightenment.

The second library that fulfills Wilson’s vision is the Barbara Goldsmith Rare Book Room at the American Academy in Rome, and that’s where I come in. In addition to writing, my passion has been the conservation and preservation of the written word. After years of training, I have become an expert in techniques on how to build a proper 21st Century library. I have worked with the conservation and preservation units at the New York Public Library and New York University, and have consulted for the Wellesley College Library, the Morgan Library among others.

At the American Academy book room in Rome the architecture was designed by Michael Graves but my role was the technology: There are no noxious sealants or substances here. It is precisely air and temperature controlled. Even the hardware is specially designed so that the books can be smoothly removed from the metal shelves and cabinets. All the book boxes and bookends etc. are acid-free so that there will be no deterioration. Every desk has several digital connections that can reach databases the world over. The way the books and periodicals are organized and catalogued provides the Rome fellows with swift access to what they want to read. It’s a comfortable place in which to spend time, so popular in fact that a key is provided to the fellows so that they can enter twenty four hours a day. This library now serves as a pilot project for other 21st Century libraries and even the new Vatican Library refurbishment reflects viewing it, as it is a gem of conservation and preservation techniques.

One knows that in the hands of the visionary Robert Wilson and with his tenacity, his library too, will come to fruition and it will tie together all the other functions of the Watermill Center. And now I know why he chose me, almost two decades ago, to stand in that weed-clogged meadow, looking at those desiccated buildings, on that unusually hot June day. Because I too see exactly what Robert Wilson saw so long ago.

Barbara Goldsmith – Writer and paper conservationist and preservationist.

From "The Watermill Center: A Laboratory for Performance and Robert Wilson's Legacy" published by DACO, October 2011.